Domani, 14 settembre alle 18.00 a Milano alla Fabbrica del Vapore Le Alleanze dei Corpi inaugura l’edizione 2023 con l’incontro SPAZIO PUBBLICO – SPAZIO COMUNE Soglie, spazi trasformativi, usi civici: la città come commoning, una riflessione sulla città a partire dal concetto di spazio comune, sviluppato dall’architetto e sociologo greco Stavros Stavrides, attivista e teorico dei commons, professore alla Scuola di Architettura della National Technical University di Atene (NTUA).

Stavros Stavrides sarà in dialogo con Annalisa Metta, Emanuele Braga, Alessandro Bollo, Marco Minoja ed Elisabetta Consonni, riportando le sue ricerche sui movimenti sociali urbani, sulla giustizia spaziale e sugli spazi di soglia nell’esperienza della metropoli. Tra i suoi libri più recenti, tradotti in molte lingue, Suspended Spaces of Alterity (2010), Towards the City of Thresholds (2010), Common Spaces of Urban Emancipation (2020). SPAZIO COMUNE è stato recentemente tradotto e pubblicato in Italia da Agenzia X. Emanuele Braga e Maria Paola Zedda lo hanno intervistato intorno a cinque assi abitare; comunità, istituzioni, real estate, ecologie.

ABITARE

Emanuele: Iniziamo con una domanda di rito: come stai? Qui a Milano gli studenti dormono in tenda davanti alle università perché gli affitti delle case sono troppo alti. Il settore privato che dice di fare Social Housing riceve fondi pubblici, per poi preparare studentati di lusso al prezzo di 450€ al mese per un letto in una camera condivisa. La polizia pochi giorni fa ha sgomberato un palazzo occupato nel quartiere di Nolo. Ci abitavano tutti lavoratori. Commessi, receptionist, riders, muratori. A Milano anche chi ha un lavoro e guadagna più di 1000€ al mese è costretto a occupare una casa. Figuriamoci chi il lavoro non ce l’ha. Viviamo in una città in cui il costo della vita è del tutto sproporzionato rispetto alla distribuzione di ricchezza per la maggior parte degli abitanti. Tu hai scritto un libro con Penny Travlou sull’abitare come costruzione di commons, osservando come nel mondo diverse comunità affrontano il problema che abbiamo qui a Milano con strategie di resistenza alternative. Ci spieghi cosa hai scoperto?

Stavros: Il problema degli alloggi è molto sentito anche in Grecia. La finanziarizzazione del mercato immobiliare ha creato un’immensa pressione su coloro che sono indebitati a causa dei mutui immobiliari. Inoltre, l’avanzare della turisticizzazione – soprattutto ad Atene – ha fatto salire alle stelle gli affitti e ha costretto molti a cercare alloggi a prezzi accessibili in quartieri lontani. Le piattaforme tipo Airbnb hanno contribuito notevolmente a questo processo, cambiando il carattere del centro. Durante la crisi del debito pubblico (che colpisce ancora molto l’economia greca) l’unica organizzazione che forniva alloggi sociali è stata chiusa e il suo capitale è stato utilizzato per pagare parte del debito pubblico, il che, tra l’altro, è ingiusto e socialmente distruttivo. Pubblicando la raccolta Housing as Commons (composta per lo più da articoli commissionati) ci siamo posti l’obiettivo di stabilire una visione dell’alloggio che lo consideri un bene comune da liberare dalle priorità del mercato e dalle scelte di governance neoliberiste. Siamo riusciti a scoprire che in molte parti del mondo si sviluppano importanti lotte per l’abitare con questa prospettiva, implicita o esplicita. Esploriamo quindi casi di progetti abitativi informali che producono infrastrutture e pratiche quotidiane comuni, così come esperienze rilevanti che provengono da cooperative edilizie, squat e lotte per il diritto alla casa. Come concludiamo nella nostra introduzione, “per mantenere il potere trasformativo della comunanza, è importante combinare sempre le esperienze di comunanza con forme di organizzazione sociale che resistano sia al potere del mercato sia al dominio dello Stato”

COMUNITA’

Maria Paola: Spazio comune ha come sottotitolo la città come commoning, una definizione che insiste sulla differenza tra commons e commoning ponendo un accento sul processo, su un tempo in divenire, su una progressività e quindi sul tempo delle pratiche. Li definisci in modo mobile, ossia come cantieri collettivi di ibridazioni. Quali tempi per questi spazi?

Stavros: Credo che reclamare il diritto alla città significhi reclamare la città come bene comune, cioè reclamare il potere emancipatorio della creatività collettiva: reclamare la “città come azione”. (per seguire il suggerimento di H. Lefebvre). Lo spazio comune è sia un ambito esplicito del commoning urbano sia uno dei suoi più importanti fattori di formazione. Lo spazio comune accade: viene eseguito piuttosto che stabilito come disposizione spaziale permanente. Ciò significa che gli spazi comuni esistono finché le persone li producono e li mantengono attraverso le pratiche del commoning urbano. Lo spazio comune esprime il potere che ha la condivisione di creare nuove forme di vita in comune. Naturalmente non c’è garanzia che tali spazi mantengano il loro carattere. C’è sempre il pericolo che questi spazi vengano chiusi dalla comunità che li ha inizialmente creati. Credo che la forza del commoning risieda nella porosità che stabilisce nello spazio comune. La porosità dà ai nuovi arrivati l’opportunità di unirsi e di contribuire allo sviluppo del commoning. Gli spazi comuni devono essere eseguiti dalle pratiche delle comunità aperte di commoner.

ISTITUZIONI

Maria Paola: Scrivi “gli spazi comuni sono spazi prodotti nel tentativo di creare un mondo condiviso che ospiti, sostenga, esprima una comunità”. Questo slittamento evidenzia un’importante questione. La differenza tra la proprietà e l’uso. Quali possibilità hanno le istituzioni culturali pubbliche di divenire o essere percepite come spazio comune, senza appropriarsi e usurpare il concetto di bene comune?

Stavros: C’è sempre il rischio di presentare come comuni quegli spazi che sono offerti al pubblico ma che rimangono sotto il controllo di una certa autorità pubblica. Come dimostra l’esempio di Napoli, perché gli spazi comuni rimangano tali è necessario sviluppare forme di autogestione che li sostengano. Il commoning può emergere come un modo di produrre e utilizzare lo spazio urbano distinto dalla logica capitalistica solo finché si confronta sia con le regole imposte dal mercato sia con le premesse della governance capitalistica.

REAL ESTATE

Maria Paola: Dei tuoi scritti mi ha sempre fornito una fonte di ispirazione la relazione tra spazi e pratiche, la riflessione sulla loro interdipendenza, e su come gli spazi siano generativi degli immaginari e di conseguenza delle lotte e delle pratiche di resistenza. L’urbanistica o l’architettura, non solo dal punto di vista teorico, forniscono oggi gli strumenti per la creazione degli spazi di soglia, o almeno per la loro tutela? E dall’altro punto di vista, come liberare, recuperare spazi in una città che imposta la sua pianificazione con un funzionalismo produttivo, mirato alla privatizzazione, al profitto e allo sfruttamento del suolo?

Stavros: Come suggerisco in un articolo pubblicato di recente, “abbiamo bisogno di sforzi per ricollegare l’architettura alle pratiche di condivisione dello spazio. A partire da queste pratiche, gli architetti possono concepire e suggerire modi per incoraggiare e sostenere la comunanza attraverso e nello spazio abitato. Uno scambio reciproco di esperienze, competenze, conoscenze e saggezza acquisite nella pratica tra esperti e abitanti delle città può dare forma ai contorni del commoning urbano” (Stavros Stavrides (2023) Common space creation: can architecture help? (Towards a provisional manifesto), The Journal of Architecture, 28:1, 154-168, DOI: 10.1080/13602365.2023.2179097). Gli spazi comuni di soglia possono essere creati con l’aiuto di esperti (o assistenti tecnici, come li chiamano i movimenti dei senzatetto brasiliani), ma è la lotta della gente comune che può garantire il loro carattere comune e la loro proliferazione nella città. Inoltre, è importante sviluppare immaginari che si discostino dalle rappresentazioni dominanti dello spazio urbano. Gli spazi possibili possono diventare il mezzo per immaginare e sperimentare forme di organizzazione sociale basate sulla mutualità, l’uguaglianza e l’assistenza inclusiva.

ECOLOGIE

Emanuele: Fra un mese a Milano si terrà Il WCCJ (Congresso mondiale per la giustizia climatica) in cui converranno i principali movimenti per il clima. L’Italia come la Grecia e il resto del Sud dell’Europa negli ultimi anni passa ormai quotidianamente dall’incendio, alle alluvioni ai tornadi con conseguenze catastrofiche per commons come l’acqua, l’ecosistema vegetale e animale, l’agroecologia. Pensi che il movimento per i commons del prossimo decennio sarà protagonista nei movimenti per il clima?

Stavros: Sì, credo di sì. Di recente ho visitato la Colombia e ho incontrato gli attivisti dei movimenti per l’abitare. Sono rimasto davvero stupito dal loro profondo coinvolgimento nelle lotte contro le politiche che hanno creato i catastrofici cambiamenti climatici. Vivendo in condizioni estremamente precarie (con inondazioni e piogge abbondanti che minacciano i loro insediamenti abitativi informali), dicono: Sentiamo il cambiamento climatico nelle nostre lotte per la sopravvivenza quotidiana. Siamo noi più di chiunque altro a poter dire quanto siano distruttive e ingiuste le politiche che sostengono l'”estrattivismo” (incluso l’estrattivismo urbano, cioè l’estrazione di profitti dalla chiusura delle infrastrutture urbane). Le lotte per proteggere la natura e per sostenere forme di convivenza che non minaccino la vita delle generazioni future sono lotte ispirate ai valori e alle esperienze del commoning.

English Version

HOUSING

Emanuele: Let’s start with a customary question: how are you? Here in Milan, students are sleeping in tents outside universities because rental prices for housing are excessively high. The private sector, claiming to provide Social Housing, receives public funds and then offers luxury student accommodations at a cost of €450 per month for a shared room. The police recently evicted an occupied building in the Nolo neighborhood. It was home to workers, including salespeople, receptionists, delivery riders, and construction workers. In Milan, even those with jobs earning more than €1000 per month are forced to occupy housing. Imagine the unemployment! We live in a city where the cost of living is entirely disproportionate to the distribution of wealth for most residents.

You co-authored a book with Penny Travlou on housing as a process of commoning, observing how different communities around the world tackle the issue we have here in Milan with alternative resistance strategies. Could you explain what you discovered?

Stavros: The housing problem is very acute in Greece too. Financialization of the housing market has created an immense pressure on those indebted because of housing loans. Also, advancing touristification – especially in Athens – has skyrocketed rents and has forced many to search for affordable housing in faraway neighborhoods. Airbnb-type platforms have greatly contributed to this process by changing the character of the dowtown neighborhoods.

During the public debt crisis (which still affects greatly Greek economy) the only organization providing social housing was closed down and its capital was used to pay part of the public debt, which, by the way, is unjust and socially destructive.

Publishing the collection Housing as Commons (of mostly comissioned articles) we were aiming at establishing a view towards housing that considers it a common good to be freed from market priorities and from neoliberal governance choices. We were able to discover that important housing struggles develop in many parts of the world with such a perspective, implicit or explicit. Thus we explore cases of informal housing projects that produce commoning infrastructures and commoning everyday practices as well as relevant experiences that come from housing cooperatives, squats and struggles for the right to housing. As we conclude in our introduction, “In order to retain the transformative power of commoning, it is important to always combine experiences of commoning with forms of social organization that resist both the power of the market and the domination of the state”.

COMMUNITIES

Maria Paola: Common Space has as its subtitle the city as commoning, a definition that insists on the difference between commons and commoning by placing an emphasis on process, on a time in the making, on a progressiveness and therefore on the time of practices. You define them in a mobile way, i.e. as collective sites of hybridisation. What timescales for these spaces?

Stavros: I believe that reclaiming the right to the city means reclaiming the city as commons, that is, reclaiming the emancipatory power of collective creativity: reclaiming the “city-as-oeuvre”. (to follow H. Lefebvre’s suggestion). Common space is both an explicit scope of urban commoning and one of its most important shaping factors. Common space happens: it is performed rather than established as a permanent spatial arrangement. This means that common spaces exist as long as people produce and maintain them through practices of urban commoning. Common space expresses the power commoning has to create new forms of living-in-common. Of course there is no guarantee that such spaces will retain their character. There is always the danger of those spaces being enclosed by the community that has initially created them. I believe that the power of commoning lies in the porosity it establishes in common space. Porosity gives to newcomers the opportunity to join in and to contribute to the development of commoning. Common spaces need to be performed by the practices of open communities of commoners.

INSTITUTIONS

Maria Paola: You write “communal spaces are spaces produced in an attempt to create a shared world that hosts, sustains, expresses a community”. This shift highlights an important issue. The difference between property and use. What possibilities do public cultural institutions have to become or be perceived as common space, without appropriating and usurping the concept of the common good?

Stavros: There is always the risk of presenting as common those spaces that are offered to the public but remain under the control of a certain public authority. As the Napoli example shows, for common spaces to remain as commons there need to be developed forms of self management which will sustain them. Commoning may emerge as a way of producing and using urban space distinct from capitalist logic only as long as it confronts both the marketimposed rules and the premises of capitalist governanance.

REAL ESTATE

Maria Paola: In your writings, I have always been inspired by the relationship between spaces and practices, the reflection on their interdependence, and how spaces are generative of imaginaries and consequently of struggles and practices of resistance.

Does urban planning or architecture, not only from a theoretical point of view, provide today the tools for the creation of threshold spaces, or at least for their protection? And from the other point of view, how to liberate, to recover spaces in a city that sets its planning with a productive functionalism, aimed at privatisation, profit, and land exploitation?

Stavros: As I suggest in an article published recently “We need efforts to reconnect architecture to practices of space commoning. From those practices, architects may conceive and suggest ways to encourage and support commoning through and in inhabited space. A mutual exchange of experiences, skills, knowledge, and wisdom acquired in practice between experts and urban dwellers may shape the contours of urban commoning” (Stavros Stavrides (2023) Common space creation: can architecture help? (Towards a provisional manifesto), The Journal of Architecture, 28:1, 154-168, DOI: 10.1080/13602365.2023.2179097). Threshold commoning spaces can be created with the help of experts (or technical assistants as the Brazilian homeless movements call them) but it is the struggle of everyday people that may ensure their commoning character and their proliferation in the city.

Also, it is important to develop imaginaries that depart from the dominant representations of urban space. Possible spaces may become the means for both envisioning and testing forms of social organization based on mutuality, equality and inclusive care.

ECOLOGIES

Emanuele: In a month, Milan will host the World Congress for Climate Justice (WCCJ), where the main climate movements will converge. Italy, like Greece and the rest of Southern Europe, has been facing daily wildfires, floods, and tornadoes in recent years, with catastrophic consequences for commons like water, the plant and animal ecosystem, and agroecology. Do you think that the commons movement in the next decade will play a leading role in climate movements?

Stavros: Yes, I believe so. Recently I visited Colombia and met with activists of housing movements. I was really amazed by their deep involvement in struggles against the policies that have created the catastrophic climate changes. Living in extremely precarious conditions (with floods and heavy rains threatening their informal housing settlements), they say: We feel climate change in our struggles for everyday survival. It is us more than anybody else who can tell you how destructive and unjust are the policies that support “extractivism” (urban extractivism – the extraction of profit from the enclosure of urban infrastructures – included). Struggles to protect nature and to support forms of living together that do not threaten the life of future generations are struggles inspired by the values and experiences of commoning.

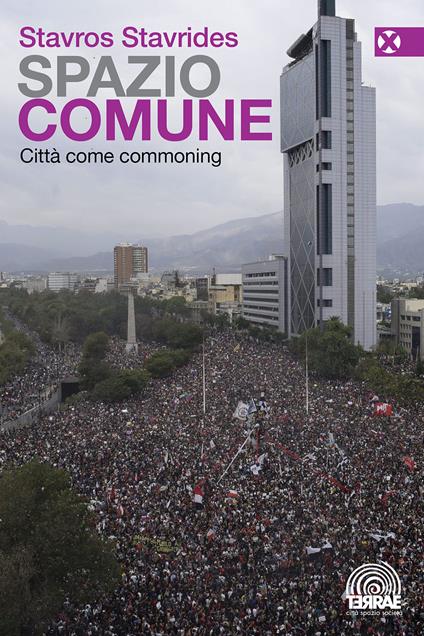

Immagine di copertina da Unsplash